Net Zero / Decarbonization Is Not a Strategy - It’s a Religion

Notes From My Weekly Feed # 7: An Essay on the Religion of Net Zero and a Few Thoughts on What is an Emerging Technology

An Essay On The Religion of Net Zero

“Energy transition / Net Zero / Decarbonization” has become a belief system.

Energy transition - like religion in the Middle Ages - has become a topic where even asking the wrong question can get you metaphorically (or socially) burned at the stake. Many people don’t just believe in net zero - they’re devoted to it. And like any belief system, it comes with a set of commandments you’re not supposed to question:

2050 net-zero targets are sacrosanct

Any deviation from those goals is heresy

Externalities justify anything

Over the past three years, I’ve watched the same people who once declared 2050 “non-negotiable” slowly walk back their certainty. Now it’s 2060. Or 2075. Or even 2100. Take your pick.

Instead of reassessing the underlying strategies, we’re just doubling down - spending more, distorting more, and pretending we can out-spend thermodynamics.

And this is now guiding corporate strategy, investor capital allocation, and global policy.

The Unintended Consequences of Urgency

However, every policy decision has two effects: (1) the one you plan for (2) and (many times) the one you don’t.

The (planned) goal of net-zero policies is noble: reduce emissions, save the planet, protect the future generations. But in our rush to get there yesterday, we have overlooked some of the unintended side effects in:

Higher energy prices

Fragile energy grids

Widening fiscal deficits

Growing dependence on unfriendly regimes

If we’re honest, most of the decarbonization playbook is built on two assumptions: (1) under-estimating tradeoffs and (2) and that we can centrally plan innovation.

We’ve put so much weight on net zero that it has become the only objective worth pursuing. That’s dangerous. Because once decarbonization becomes the only lens, we stop asking other critical questions.

Questions that matter just as much, if not more.

Here are three questions that I try to ask myself when evaluating an early stage energy technology.

Is it more promising than incumbent options? In Energy Transition, promising usually means more energy dense and abundant. Every historical energy transition - wood to coal, coal to oil, oil to gas - was driven by the novel fuel being superior to the incumbent on at least one if not both.

Is the capital generating strong returns for the investors? Net-zero does not work if investors lose money. And remember, by investor i dont just mean multi-billion dollar banks / funds but the folks whose money they are investing - these include teachers, policeman, firefighter, yours and mine

Is there net benefit to society at large? This one is often used to justify the net-zero dogma and we enter the “The Externality Trap”. Externalities have become a catch-all justification: “We’re saving the world. The numbers don’t matter.”

We need all three to make the system work. But let’s start with the third one first, since that is used to justify everything in the religion of net-zero.

The Externality Trap

Valuing externalities - especially over a 50–100 year horizon - is incredibly subjective. You’re projecting:

The pace of global warming

Its impact on human society

The knock-on effects on economies, health, migration, conflict etc.

And then discounting all of that back to today

Anyone who’s run a DCF knows how wildly sensitive the output is to assumptions. Change only one parameter, say the discount rate by 1%, and you can swing billions in valuation. Now do that over 100 years, across compounding uncertainty. The intellectual scaffolding collapses under its own weight.

But let’s assume the models are “right.” Let’s say climate change will cause real harm in 50-100 years, just as many in the net-zero industrial complex would argue. Even then, we need to ask: What’s the cost of the policies today by pursuing these policies aggressively? Are we:

Sacrificing economic development today?

Limiting energy access for the world’s poor?

Handicapping industries?

Choosing symbolic climate gestures over actual human well-being?

Inadvertently turning “Energy” into a political topic and thus driving decisions based on beliefs and emotions rather than facts and realities?

If the answer to any of those is yes, then we deserve a real debate about priorities. Debate on tradeoffs. Which technologies merit investment and our attention. And we must be willing to revise our assumptions as-needed and over time, as the world changes.

The IEA and others love to forecast the future in fixed scenarios. But innovation does not follow a roadmap. The most important breakthroughs often arrive unannounced.

The goal isn’t to predict the future, as the net-zero industrial complex does every year - it’s to build a framework for spotting and nurturing asymmetric technology bets when they appear.

Let me be clear: I’m not against renewables. I’m against energy scarcity.

I believe in coal, gas, solar, wind, nuclear - all of it. Because every geography, use case, and infrastructure system is different. Trying to force-fit one solution into every region is how you get de-industrialization and geopolitical dysfunction.

What Are the Right Bets?

So, what bets do we want to take when it comes to Energy Transition? That’s what this essay is really about.

Are we betting on decarbonization at all costs - no matter the tradeoffs?

Or do we instead want to bet on energy modernization and abundance?

For a long time it has felt like we’ve chosen the former. Net zero has become the north star. The organizing principle. The altar.

But should it be?

Is net zero one of our top 10 societal priorities? Maybe. Top five? I doubt it. Top three? Definitely not.

And if we’re going to commit trillions of dollars based on projections 50 or 100 years out - with enormous standard deviations - on the name of externalities and its impact on planet 50 - 100 years out, we should at least consider: What other social cause could that money be solving today?

Solving poverty

Curing diseases

Building infrastructure where its most needed

Educating kids

It’s not all of the above and decarbonization. We do not have infinite capital. But we can strive for infinite energy - of all forms and kind - with the limited capital we do have.

We’ve taken a well-meaning goal - decarbonization - and inflated it into a doctrine. What we need now is a sincere perspective and recalibration. And i think, the recalibration has begun (hopefully).

What is an Emerging Technology

This post was inspired by someone passionately referring to wind energy as an emerging technology. So I thought it may be an interesting post to define what is an emerging technology from an investor perspective at least.

The easiest way to define it is to follow the money. Specifically - what kind of capital is funding the technology? Venture capital or project finance / debt?

Today, solar and wind are not emerging technologies. They’re mature. They’re approaching theoretical efficiency limits. Most of the R&D today is incremental. And they’re financed like infrastructure, not startups. The capital inflow is from infra investors and project finance underwriting to a 8-12% IRR. That’s not a bad thing - solar and wind absolutely deserve investment, especially when backed by long-term PPAs and structured properly. I personally am bullish on Solar for behind the meter distributed generation systems that dont really need PPAs.

But you won’t see venture dollars chasing solar and wind. Why? Because the economic upside is capped. Venture capital hunts for 100x+ returns, which typically means:

The technology is nascent

The market is barely tapped

The risks (and rewards) are asymmetric

Still unsure how to tell the difference? Try this:

Mature Tech → Look at portfolios of infrastructure investors like Ara Partners

Emerging Tech → Look at portfolios of early-stage VCs like New Climate Ventures

You may disagree, but I think it’s pretty straightforward once you trace the capital stack.

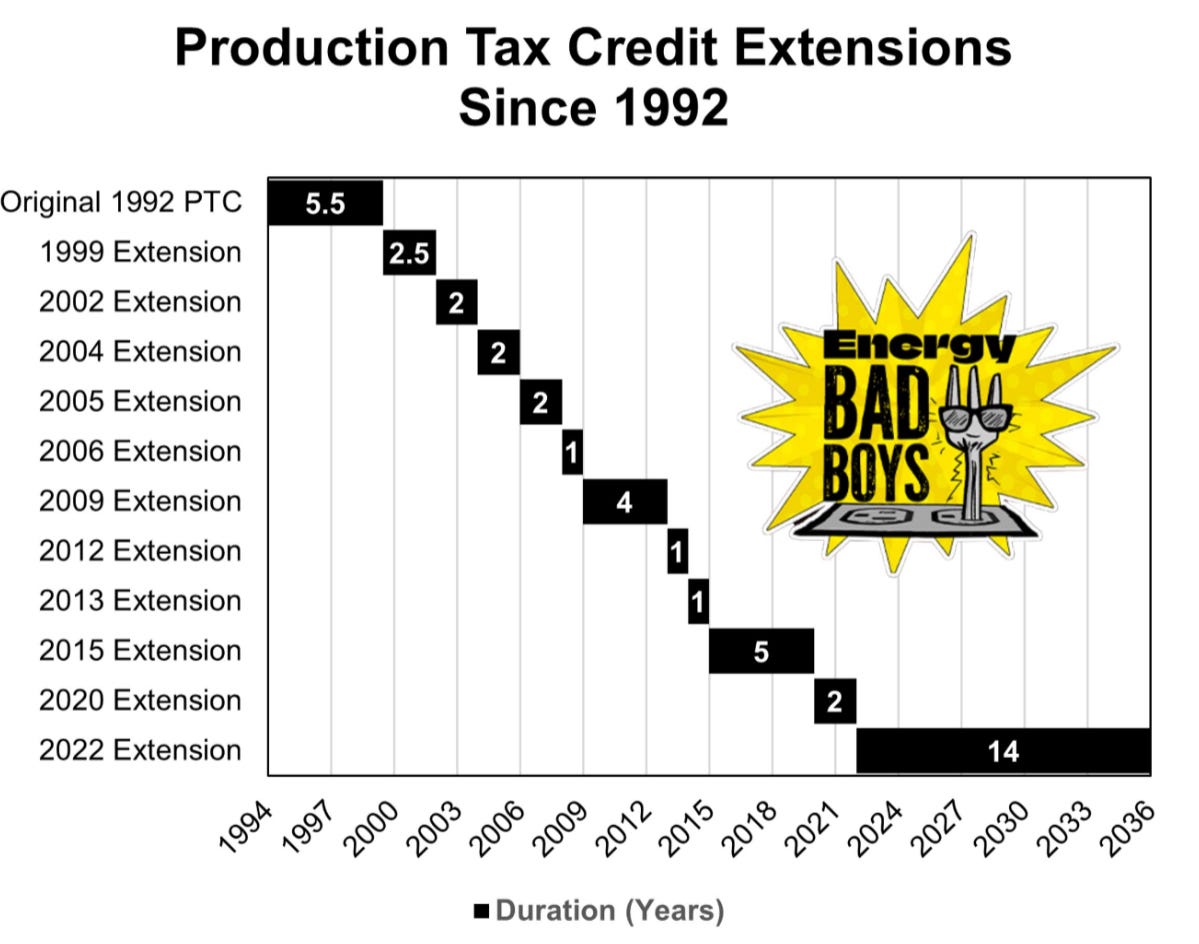

Now, why do some still label wind and solar as emerging? Usually for political or subsidy reasons. Emerging technologies tend to qualify for tax credits and government support. Wind and solar were emerging back in the ’90s, when subsidies first helped them scale. But those “temporary” tax credits have been extended again and again (see chart below—credit to Energy Bad Boys for their no-bull takes on energy).

So we end up in a weird place: wind and solar are mature tech, yet treated like emerging tech in policy. In cricket parlance, wind and solar are the Shahid Afridi of the renewable industry - they never age.