Notes From My Weekly Feed #3

Updated Musings on Social Media, Flag Burning and Desecration, The Real Reason Indians are Lost and AI’s Verbal Flood…

Echo Chambers Weren’t the Problem — Until Social Media Made Them Dangerous (Substack - Noah’s Opinion)

I think most people would agree that we’ve become more divided and politically intolerant—but what’s really driving it? Like everyone, I had a hypothesis of my own, and reading Noah’s blog helped me update and refine my own hypothesis.

Much like Noah Smith, my hypothesis was that maybe social media has a role to play in this - but in a much different way. Living in Houston, I may have had a different vantage point than those on the coasts. My natural proclivity is towards liberal talking points, but living in Houston I am exposed to opposing viewpoints often enough. My social media diet may be liberal, but my in-person interactions throw opposing viewpoints frequently enough. This happens to many in Houston, but I have seen two different ways that my peers react to it.

Most of my peers and close friends are liberal for the large part and would feel as much at home in Berkeley as they do in their ideological islands in Houston. However, some find non-liberal beliefs morally repulsive and find it extremely difficult to even engage with those holding such thoughts. I found this surprising, because living in Houston as a liberal, you are exposed to conservative thoughts often enough that, I thought, you would rationally take a step back as a liberal and try to understand why some people think differently, and over time start to appreciate other viewpoint on its own merit without sneering at it as some coastal liberals tend to.

So my efforts were directed to understand how a Houston liberal can demonstrate traits common amongst liberal extremists more commonly found on the coasts.

I hypothesized that people spend too much time on social media and that the social media algorithms push you into the “echo chamber” you like to live in. As such, your existing view of the world gets even more deeply embedded through positive reinforcement from your echo chamber. So by the time you hear an opposing view - after multiple sessions of positive reinforcement of your existing view - you find this new opposing view indigestible and flat-out wrong.

And in Houston, as a liberal, you’d probably get this opposing viewpoint in an in-person interaction - and you are meeting someone in-person outside of professional boundaries only a few times per week. So while you lived in your echo chamber for the rest of the week, consuming several tiny positive reinforcements multiple hundred to thousand times a week while scrolling through your personalized Reddit, Instagram, Twitter, Youtube or Facebook feed, you encountered the altering viewpoint only once, maybe twice, in an in-person interaction. Therefore, that in-person interaction just seemed wrong to you - and the person offering that counter-argument seemed stupid at best and morally offensive at worst.

So I hypothesized that social media’s echo chamber has essentially conditioned a person’s brain to simply reject an opposing viewpoint when that viewpoint is encountered in person.

But then I came across this piece by Noah Smith, and I think he made a more insightful argument - one that also applies better to a different group of people, perhaps people not living in places like Houston - but also to those living in geographical echo chambers (i.e. a Liberal in Berkeley or a Conservative in Houston). He first contends that “echo chambers” were actually functional, maybe even healthy, in the pre-social-media age.

“Geographic sorting acted as a sort of release valve for the social tensions that built up in the United States after the turbulent 1960s and 1970s. Instead of constantly feuding with their conservative neighbors about abortion or gay marriage or Ronald Reagan, liberals could just move — to San Francisco or New York or L.A. if they had money, or to Oregon or Vermont or Colorado if they didn’t. There, they would never have to talk to anyone who loved Reagan or thought homosexuality was a sin.

Albert Hirschman wrote that everyone has three options to deal with features of their society that they don’t like. You can do nothing and simply endure (“loyalty”), you can fight to change things (“voice”), or you can leave and go somewhere else (“exit”). The ructions of the 60s and 70s were a form of “voice”, but riots and protests and constant arguments about Watergate were no fun. Because Americans had cars and money, many of them could take a more attractive option: exit. In the red-blue America that emerged after the 60s, Blue Americans could move to blue states and blue cities, and Red Americans could do the opposite”

This sorting, Noah argues, made people feel less anxious - even if they weren’t exposed to opposing views, they were at peace:

“A hippie in Oakland and a redneck in the suburbs of Houston both fundamentally felt that they were part of the same unified nation; that nation looked very different to people in each place. Californians thought America was California, and Texans thought America was Texas, and this generally allowed America to function… Red America and Blue America became echo chambers that helped to contain America’s rising cultural and social polarization.”

But then, social media broke down those echo chambers—and not in the idealistic, “more dialogue for all” way. It did the opposite: it shattered geographical insulation and replaced it with a far more hostile and performative kind of exposure.

“Like some kind of forcible hive mind out of science fiction, social media suddenly threw every American in one small room with every other American… The sudden collapse of geographic sorting in political discussion threw all Americans in the same room with each other… Social media made exit impossible… Thrown into one small room with each other, they began to complain and fight… No physical-world geographic sorting can solve this. People still move to Texas to escape California’s progressive culture, but the people who move are all still on the same apps.”

So depending on where you were geographically before social media - whether in (1) a large geographical echo chamber (e.g. a liberal in San Francisco or a conservative in Houston), or (2) a small ideological island within the opposite geography (e.g. a liberal in Houston or a conservative in San Francisco) - social media made your life a bit more miserable, but through different mechanisms.

(1) In Large Geographical Echo Chambers (Example Liberal in SF or a Conservative in Houston): This is where I think Noah’s point shines. If, pre-social media, you were comfortably situated in a physical echo chamber, you were suddenly forced to contend with opposing viewpoints online. That exposure felt like a violation - an emotional “microaggression” - where the safety of ideological insulation gave way to confrontation.

(2) In Island Echo Chambers (Example - Liberal in Houston, Conservative in SF): In these settings - where you already lived with friction - social media didn’t shock you with the existence of opposing views, but it still skewed your perception of them. While you already engaged in real-world conversations with people who disagreed with you, the digital world amplified those disagreements in emotionally charged, mocking, or moralistic tones. Even if your real-world interactions were civil, social media made the opposing side look villainous, making it harder to maintain empathy in person. Social media doesn’t just keep people in their ideological bubbles - it also drags them out in the most inflammatory way possible, exposing them to “the other side” through content designed to provoke rather than persuade. Think of those viral videos labeled “liberal gets owned by X” or “conservative destroyed by Y” - they’re not invitations to understand, but performances meant to ridicule. Do we then maybe aim to “destroy” / “own” / “cancel” those with opposing view when we meet them in person?

So while both Noah and I attribute blame to social media for our social division, I think Noah makes a compelling argument about how those who already lived in physical echo chambers were suddenly forced to contend with opposing viewpoints online - while my hypothesis probably applies more to environments like Houston, where ideological mixing is more common but still vulnerable to digital conditioning.

The old, geographically sorted bubbles made opposing ideas largely invisible. The new digital bubble, by contrast, doesn’t just show you opposing views - it mocks them, exaggerates them, and serves them up in ways that make you angry at the people who hold them.

Social media didnt divide us by building “echo chambers”, as i originally thought. It divided us by weaponizing exposure.

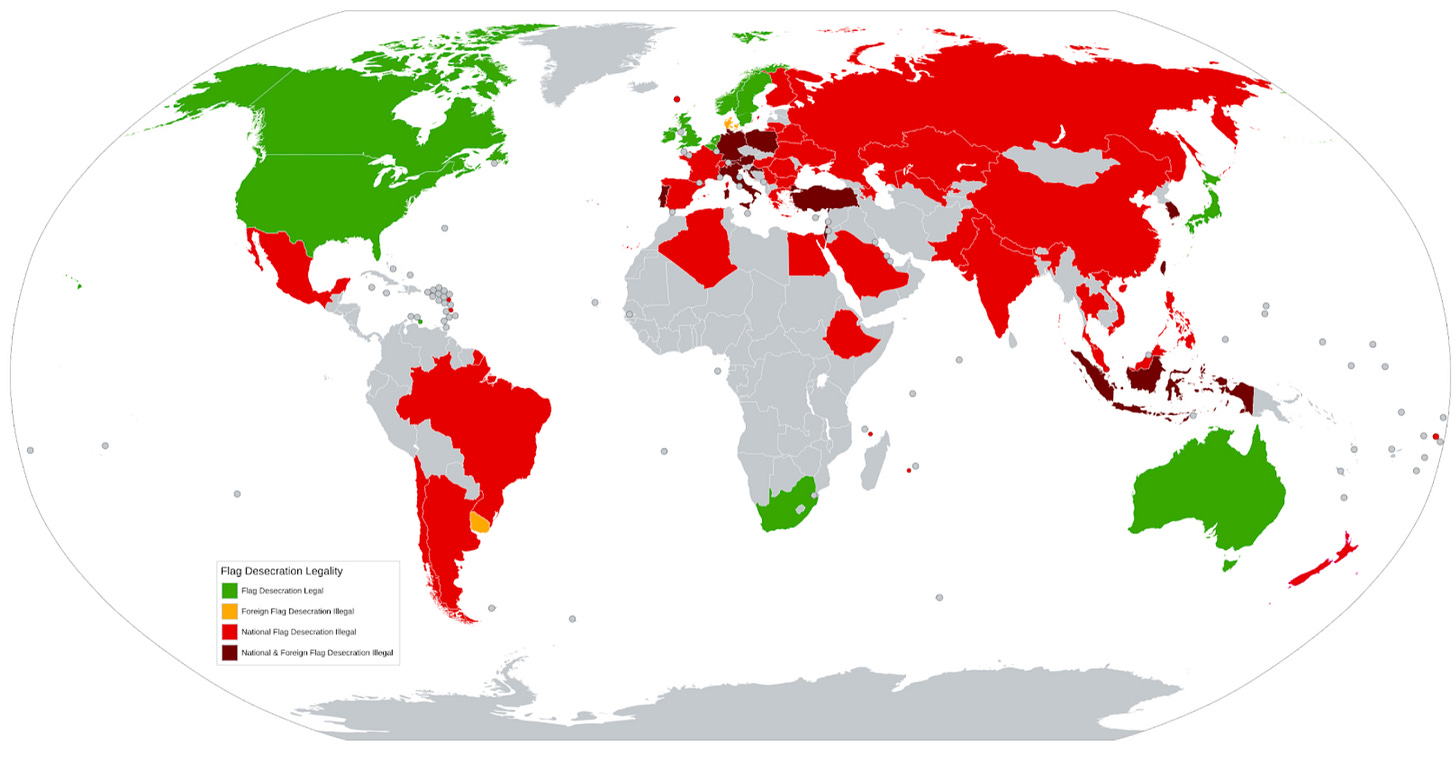

Flag Burning / Desecration Laws Across Countries (Wikipedia)

Watching protests emerge across American cities where folks were hoisting foreign flags got me thinking about flag desecration laws - specifically, what happens when you burn flags in different countries. I assumed free speech purists like the US and Canada would be outliers in protecting flag burning, while more traditional societies would criminalize it. But reading through the Wikipedia page, I found some interesting observations.

The US and Canada do treat flag burning as protected symbolic speech, but I found that most liberal European democracies - Germany, France, Italy, Austria - criminalize flag desecration with serious penalties, for example Germany will give you up to 3 years imprisonment for burning their flag. But the most intriguing case turned out to be Uruguay, which has what I think is a diplomatically brilliant approach. Burning the Uruguayan flag? Perfectly legal. Desecrating any foreign nation’s flag while in Uruguay? That’ll get you up to 3 years in prison.

I suspect this prevents diplomatic incidents when foreign leaders visit - protesters can express dissent against their own government but can’t create international crises by burning, say, the Brazilian flag during a state visit. Denmark follows similar logic, allowing Danish flag burning but criminalizing foreign flag desecration as potential “threats” to foreign relations.

I think these laws reveal less about patriotism and more about how different societies balance domestic free expression. Some countries prioritize national honor, others diplomatic pragmatism, and a select few treat flags as fair game for political protest. The irony is that some of the world’s most repressive regimes share the same basic approach to flag protection as liberal European democracies - the difference is probably in enforcement and broader speech protections, not the underlying laws themselves.

The Real Reason Indians Are Lost (The Economist)

Anyone who has spent time in India knows that Google Maps’ ability to navigate the country’s unconventional geographical address system is genuinely impressive—and here’s a fascinating video about that challenge (How Google Maps Fixed India’s Street Name Problem). However, what I hadn’t previously considered was how this quirky address system creates significant legal and financial complications that ripple through India’s economy.

The core issue lies in India’s landmark-based addressing. Since a single property can be identified by its proximity to multiple landmarks, the same house or building can legitimately have different addresses across various legal documents. This creates a verification nightmare when multiple claimants assert rights to the same property, adding yet another layer to India’s already cumbersome paper trail.

A recent article in The Economist illuminated the broader implications of this addressing chaos, revealing costs that extend far beyond the inconvenience of missed deliveries.

“Addresses in the West tend to follow a simple, hierarchical system: street name and number, district, city and post code. Indian addresses have those features and more: “next to SBI ATM”; “behind Ganesh Temple”; “near Minerva cinema… The Department of Posts estimates that there are 750m households, businesses and other such discrete locations in India.”

“Consumer sanity is not the only thing that suffers. Businesses such as logistics, deliveries and e-commerce face higher costs and lower productivity. Uber drivers squander fuel and time looking for the right place. The rural economy takes a hit from the chaos in a different way. Indian states use a mishmash of colonial and pre-colonial revenue systems. Officers called collectors, tehsildars, patwaris or mamlatdars assign khasra numbers, khatauni numbers and, in one state, something called a “7/12” to plots of land. The sub-division of plots over the decades complicates matters by adding an ever-expanding series of numbers at the start.”

“The result is that different documents have different, if similar, addresses. If a landowner wishes to mortgage a property, banks are confronted with two problems. The first is that verifying that the piece of land exists takes a lot longer and becomes more expensive, often involving sending someone to look at it. The second is a higher risk of fraud, since a landholder could take different papers to different banks for loans. That drives up the cost of capital and “creates inefficiency and delay in both the property decision and the recovery process”, says Joseph Sebastian, a venture capitalist. Dr Bhattacharya, now at MIT Media Lab in Massachusetts, estimates that the combined hit of inefficiencies created by poor addresses adds up to about 0.5% of GDP.”

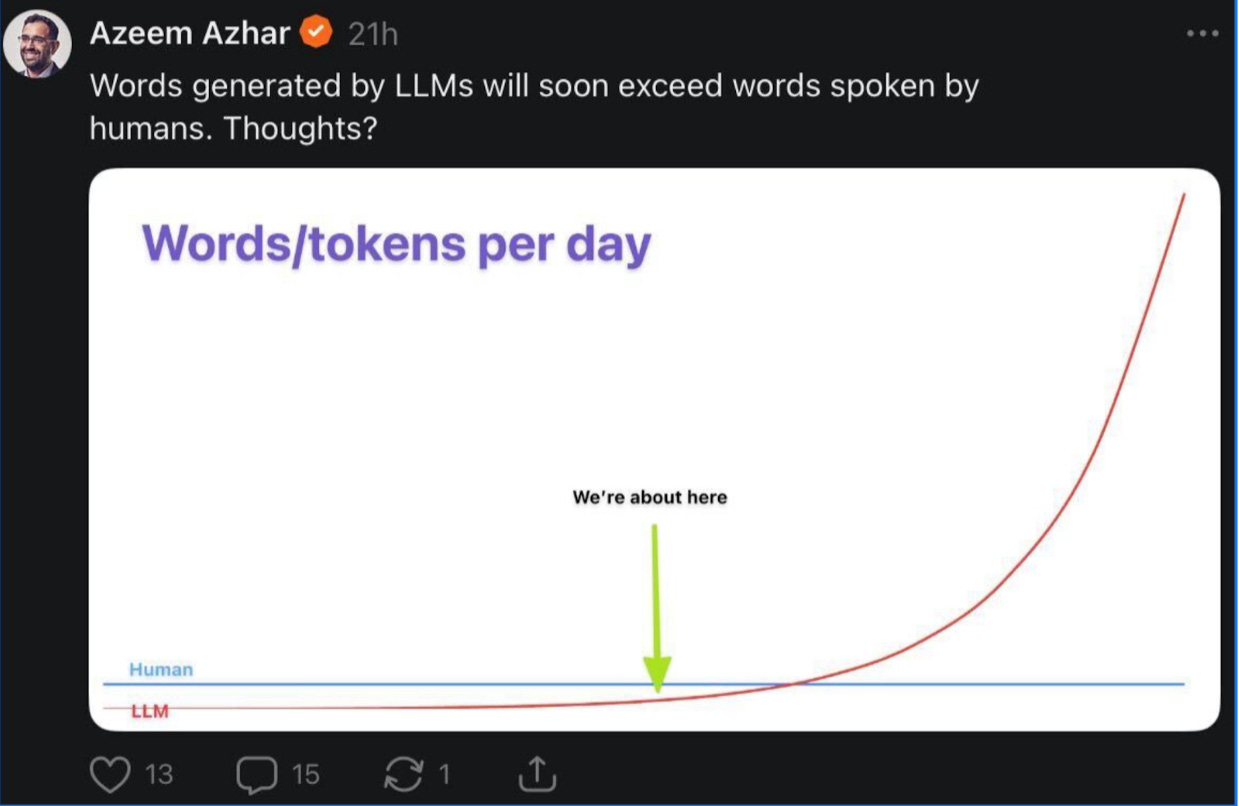

AI’s Verbal Flood - When Machines Outtalk All of Mankind

Maybe this is obvious to many, but I found it genuinely mind-blowing that the total words generated by LLMs may soon exceed all spoken words throughout human history. I’m not sure how they estimated the total words ever spoken, but it does seem plausible and simultaneously impressive.

What’s particularly fascinating to think about, though, is what this crossover actually means. Every human word spoken over 300,000 years - from a parent’s first “I love you” to a child, to Shakespeare’s soliloquies, to heated political debates that shaped nations - will soon be numerically dwarfed by machine-generated text.

The question that intrigues me is whether these new words will enhance human expression and lead to the formation of new cultural and philosophical institutions through the amplification of human thoughts, or whether we’re simply witnessing really sophisticated word-generating machines that happen to be incredibly prolific. Historically, words have always held power - they were the precursors to social and cultural revolutions. But in this new era, will words be amplified and subsequently accelerate change the same way Gutenberg’s printing press did, but even faster, or is this going to dilute the impact of words?

I suspect we’re naturally becoming more suspicious of whether words were generated by AI or authored by humans. I’m sure many of my readers wonder whether I wrote this using AI or if these are my original thoughts. If it were purely AI-generated, the seriousness with which you’d take my thoughts would probably be diminished compared to if they were genuinely my own.

For transparency: yes, I use AI, but as an assistant to help me refine my thoughts and proofread my text. As such, I happen to be in the camp that believes AI will amplify the impact of human words - what that amplification leads to is what I’m curious to find out.

See y’all next week!