What’s CRISPR, Why AI Could Not Replace Radiologists, Dam Wars, “Honey, I Bulked the Kids” and more…

Notes from My Weekly Feed # 18

A slower week on the reading (and writing) front — partly because I’ve been battling a stubborn cold while closing my first M&A deal at the new desk. Not the best combo for deep thinking, but a good enough excuse to keep things light.

This week’s post is another roundup — a mix of things I read that were too interesting not to jot down, if only so they stick a little better.

Map of the Week: Best time for fall colors across the U.S.

What Exactly Is CRISPR?

Why AI Didn’t Replace Radiologists — and a Framework to Think About Job Replacement

Hydroelectric Power Is Back — and So Are the Border Fights

Chart of the Week - “Honey - I Bulked The Kids”

TIL: Something unexpectedly impressive about Chipotle

Map Showing The Best Time To See Fall Colors

Planning a fall road trip? This national map indicates the optimal time of year to experience peak colors across the U.S.

https://smokymountains.com/fall-foliage-map/

What Is CRISPR?

I’ve been learning and writing an essay about de-extinction, and in the process have spent some time building first-principle mental models for DNA and CRISPR.

Last week was DNA - you can read that here.

As a reminder: DNA is the “codebase” - all the DNA together makes up the genome. It contains the full set of instructions for every cellular function, i.e., cell division, growth, immune response, metabolism, and more. So if any of these functions go “out of order” because of a DNA-level error, wouldn’t it be nice if you could just edit the codebase and fix the bug?

This process of “editing” the codebase and fixing the bug in the DNA is what we know as CRISPR.

One of the best primers I found is this Stanford article — worth a read if you want to dive deeper.

At a high level, CRISPR is an ex vivo gene-editing technique, meaning the editing happens outside the human body. It uses two main “ingredients”: (a) Cas9, a molecular scissor that cuts DNA at a precise location, and (b) single-guide RNA (sgRNA), a GPS-like guide that directs Cas9 to the faulty gene that needs fixing

Here’s how it works in practice — for example, in treating sickle-cell disease, the first human illness successfully cured using CRISPR (in 2019).

Doctors start by collecting hematopoietic stem cells from a patient’s bone marrow — the cells responsible for producing all blood cells. In the lab, CRISPR is programmed to target the defective gene that causes abnormal hemoglobin production. Cas9 (the “molecular scissor”) makes a precise cut in that gene, and the cell’s natural repair machinery replaces or modifies the faulty section with a corrected version.

The “fixed” stem cells are then infused back into the patient’s bloodstream, where they return to the bone marrow and start producing healthy red blood cells. Over time, these corrected cells multiply and replace the diseased ones, effectively curing the disorder at its genetic root.

CRISPR’s long-term potential is hard to overstate. Beyond rare genetic disorders like sickle-cell anemia, scientists are already exploring its use in treating heart disease, HIV, and cancer. In agriculture, it’s being tested to engineer drought-resistant crops and disease-tolerant livestock. And in environmental science, scientists are beginning to imagine how CRISPR could revive extinct traits — or even extinct species.

It’s still early days, and the ethical, technical, and ecological risks are enormous. But the fact that we now have a tool to edit the source code of life marks a turning point in how humans interact with biology itself.

Now that I’ve spent time understanding the first-principle mental models for DNA and CRISPR, I think I’m finally in good shape to finish and publish my longer essay on de-extinction soon.

Chart Of The Week - “Honey, I Bulked The Kids”

For the first time in human history, more children aged 5 to 19 are living with obesity than those who are underweight.

AI Was Supposed to Replace Radiologists. It Didn’t (Works In Progress)

We’ve all had those conversations about AI replacing jobs. And one example that’s been around forever is radiology — the idea that AI, with its superhuman image-recognition skills, would inevitably make radiologists obsolete. I’ve heard this argument (and believed it) since back when AI was still called machine learning.

In 2016, Geoffrey Hinton — computer scientist and Turing Award winner — even declared that “people should stop training radiologists now.”

Fast-forward to today: there are over 700 FDA-cleared AI models in radiology, accounting for more than three-quarters of all medical AI devices. A few, like LumineticsCore, are even cleared to operate without a physician reviewing the image at all.

So it was surprising to read this detailed essay from Works in Progress showing that, despite AI’s widespread use, demand for human radiologists has actually surged.

In 2025, U.S. diagnostic radiology residency programs offered a record 1,208 positions, up 4% from 2024, with vacancy rates at all-time lows. Radiology also became the second-highest-paid medical specialty, with an average income of $520,000 — nearly 50% higher than in 2015.

The essay outlines three reasons why radiologists aren’t out of a job — and these reasons, I think, apply to many other professions we assume AI will automate away.

Technological Bottleneck: AI models perform impressively on standardized benchmarks built from clean, well-labeled data. But real-world conditions are messier — images come from different machines, lighting setups, and patient populations. The models still work, but not always smoothly. Strong test performance doesn’t automatically mean flawless results in practice. And while this bottleneck may fade as models improve, for now, nuance matters.

Governance Bottleneck: Since nuance matters, it matters even more when legal liability is involved. Even if an AI system reads scans more accurately, who’s responsible if it’s wrong? Regulators and insurers need clear accountability before allowing autonomous diagnosis, so most AI tools are approved only as assistive technologies. This isn’t a technological limit — it’s a governance one.

Scope Bottleneck: Even when AI diagnoses accurately, it covers only a narrow slice of what radiologists actually do. Much of the job involves synthesizing results, consulting with other clinicians, and communicating with patients — tasks grounded in context, collaboration, and trust, not pattern recognition. AI may master image reading, but its scope is limited. Human judgment matters.

Together, these three bottlenecks, technological, governance, and scope, form a useful framework for thinking about whether AI will truly replace humans in any profession. The technological hurdle will likely be overcomed first. However, governance and scope are the areas where AI may face the greatest challenges in fully or meaningfully replacing humans.

Hydroelectric Power Is Back — and So Are the Border Fights

I’ve been meaning to write about this for a while, but Works in Progress beat me to it — and, candidly, did a better job than I could have.

Hydroelectricity is back in vogue. And, as always, it’s geopolitically volatile — as recent events in India, China, and Ethiopia show (more on this below).

Dams are immensely powerful pieces of infrastructure, but they also pose growing risks to those who live downstream. They are usually built for one (or more) of three reasons: to store water, generate electricity, or divert supply.

When these dams sit on international rivers, there’s no global referee ensuring upstream and downstream populations benefit equally. The builder holds all the cards.

Africa

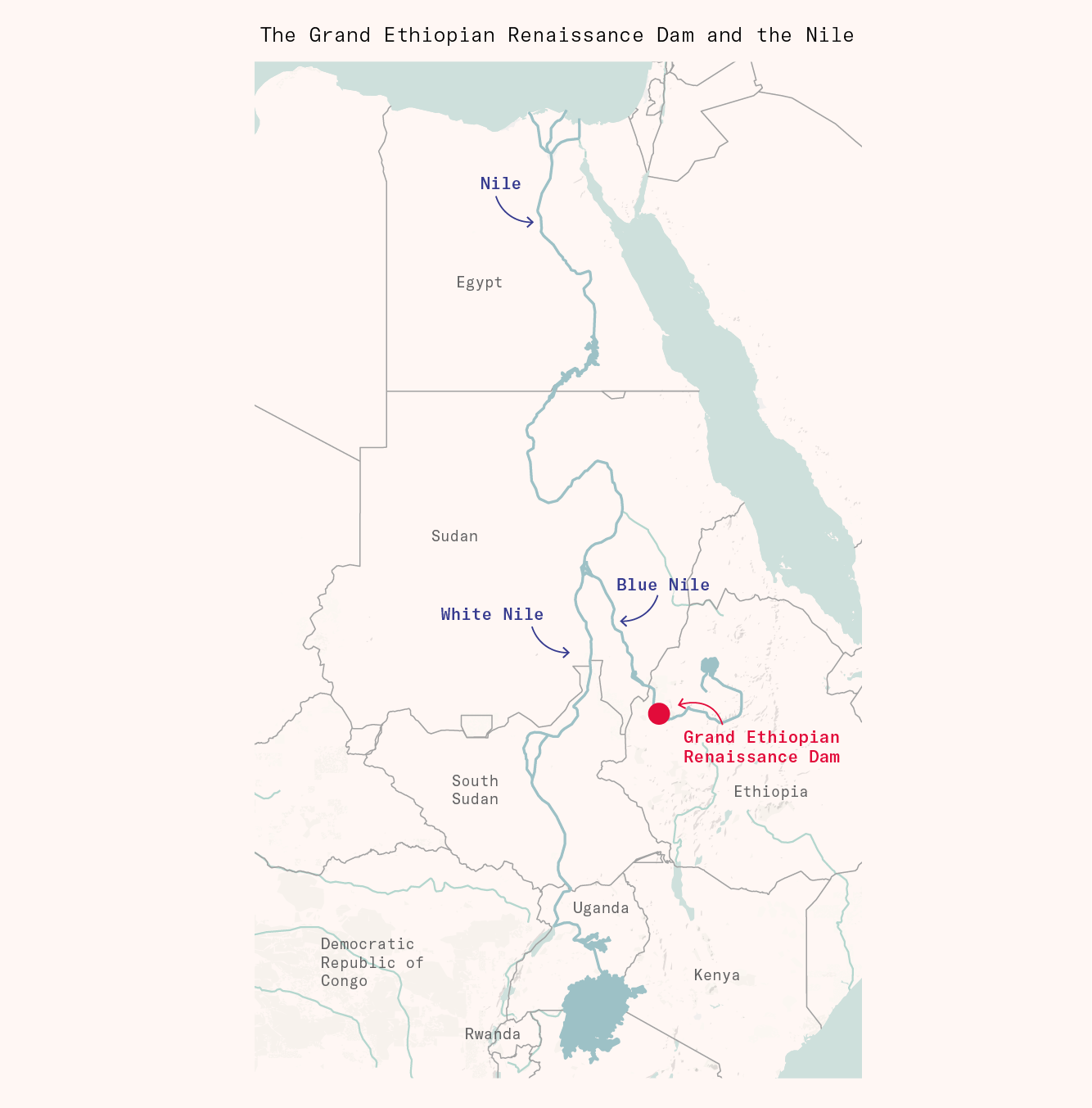

Take the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Built between 2011 and 2023, it’s one of Africa’s largest hydroelectric projects, generating 5.15 GW of electricity for Ethiopia. It sits on the Blue Nile, which provides nearly 40% of the water flowing through the greater Nile into Egypt.

The dam gives Ethiopia enormous leverage over when (and how much) water is released downstream. Release too quickly, and it could flood Sudan and Egypt, overwhelming older dams along the way. Release too slowly, and it could starve Egypt’s agricultural regions of water.

Tensions have escalated as Egypt seeks to stall the dam’s filling, while Ethiopia has reportedly deployed Russian and Israeli air defense systems to guard it from possible airstrikes.

Asia

In April 2025, India suspended the Indus Water Treaty after Pakistan sponsored an attack on Indian civilians. But without new infrastructure, India can only partially make good on its threats. To actually control — or choke — the flow, it needs more, and much bigger, dams.

Then there’s the Tibetan Plateau, source of nearly half of India and Pakistan’s major rivers, including the Ganga, Brahmaputra, and Indus. Whoever controls Tibet (cue: China) effectively controls the water supply for close to two billion people.

Even after revoking the Indus Water Treaty, India can only throttle a few days’ worth of water to Pakistan. China, on the other hand, could meaningfully constrict flows of the Ganga and Brahmaputra — affecting both India and Bangladesh.

At the center of this control lies a region called the Three Parallel Rivers, where the Mekong, Salween, and Yangtze run within just 32 kilometers of each other. The geography is extraordinary: diverting even a small portion of one river can reroute water thousands of miles away.

This is where China’s $167 billion Medong Dam project comes in — a potential engineering marvel that could also tilt the hydrological balance across much of Asia.

Here is an excerpt from Doomberg on the Medong Dam Project in China.

“With an estimated cost pegged at $167 billion, the five Medog dams would boast an eye-popping combined generating capacity of 60 GW, and produce approximately 300 TWh of power per year. From a power production perspective, this is roughly equivalent to bringing online thirty AP-1000 nuclear reactors in one go, or delivering two-thirds of all the nuclear electricity China generated in 2024… In its rush across borders toward the Bay of Bengal, the Yarlung Tsangpo River becomes the Brahmaputra in India and the Jamuna in Bangladesh. Both countries rely heavily on its flows. Understandably, they’ve expressed serious reservations about the project to Beijing. China’s position is that, because these run-of-the-river dams do not create large reservoirs in their rear, such concerns are largely unfounded. The total water flows, they argue, will remain mostly undisturbed and subject to the same seasonal variations as before… “

Doomberg then points to an excerpt from the Lowy Institute in Australia that is more skeptical than what China’s position is in the above paragraph

“India, which relies heavily on the Brahmaputra River, is likely to face serious hydrological challenges. The river provides water to Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and other northeastern states, supporting nearly 130 million people and six million hectares of farmland. If China diverts or controls the river’s flow, India could experience unpredictable floods during monsoon seasons and severe droughts in dry months. A 2024 study published in the Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs warned that China could manipulate water releases, potentially affecting India’s economic and strategic interests. Indian hydrologists have expressed concerns that sediment flow, crucial for agriculture, may be blocked by the dam, reducing soil fertility in the northeastern plain”

South America

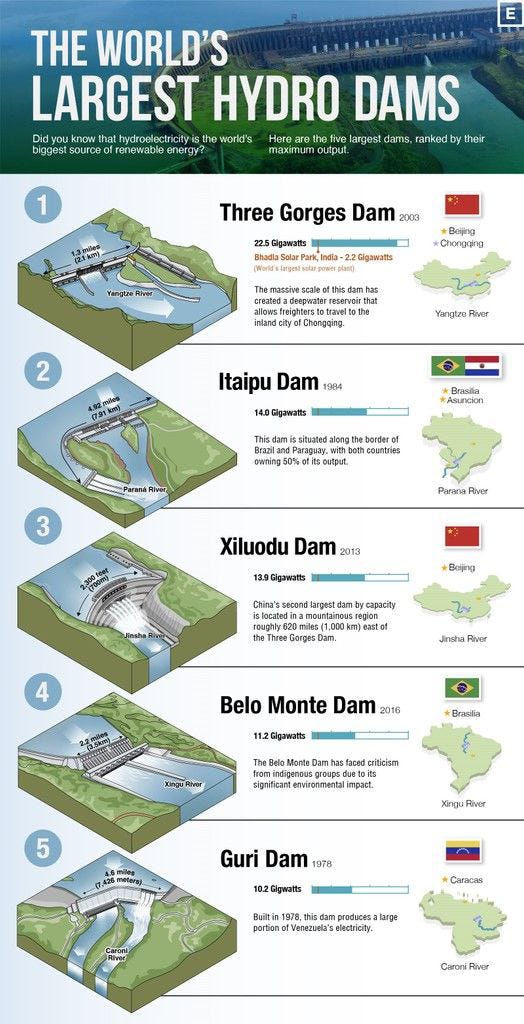

Finally, beyond Asia and Africa, there’s the Itaipu Dam, sitting on the border of Brazil and Paraguay — one of the most powerful hydroelectric facilities in the world. It’s also at the center of a fascinating (and occasionally tense) relationship between the two countries.

As Foreign Policy recently noted, Itaipu isn’t just an engineering marvel; it’s a reminder that energy can bind nations together as easily as it can divide them.

“Stretching for 5 miles across the Paraná River between Paraguay and Brazil, Itaipu is one of the world’s most powerful hydroelectric dams. In 2016 alone, the binational facility, which has an installed capacity of 14,000 megawatts, produced enough energy to meet Paraguay’s electricity demand for more than seven years.

Itaipu is the most expensive single object on Earth, according to Guinness World Records. It is also one of the most controversial — and now the center of a spying scandal that’s bringing up a bitter, decades-old rivalry.

Brazil and Paraguay built the shared dam 50 years ago to defuse a border crisis. But Itaipu’s construction was mired in deep corruption, and the final cost (including subsequent debt repayments) spiraled to more than $63 billion. Paraguayans also have long complained that the 1973 Itaipu Treaty, signed between two military dictatorships, is unfair. Notionally, the dam is a joint project, with the energy it produces split 50/50. Yet for decades, the treaty has obliged the smaller, less industrialized nation of Paraguay (population 6 million) to cede its surplus power to Brazil (210 million) at bargain-basement rates.

In 2023, both countries paid off the last installment of Itaipu’s construction debt, and key terms of the treaty elapsed. Since then, a bilateral renegotiation, conducted behind closed doors, has held out a glimmer of hope that Paraguay could wrest a more competitive price for its hydropower, along with the right to sell it to private energy providers in Brazil. Brazil, meanwhile, has sought to retain access to the cut-price energy that has supplied roughly a fifth of the country’s demand. The revision of the Itaipu Treaty is of “transcendental” importance for Paraguay, said Mercedes Canese, a former Paraguayan vice minister of mines and energy. “Brazil has harmed Paraguay enormously. This is an opportunity to see what was done wrong, correct it, and make amends.” Outside players are also taking notice of the renegotiation’s potential dividends. During a U.S. Senate hearing in May, Secretary of State Marco Rubio mentioned the talks, noting that Paraguay’s cheap, abundant power gives it an “enormous opportunity” to become a leader in artificial intelligence, encouraging “smart” investors to establish data centers in the country. This febrile mixture of geopolitical rivalry, technological competition, and historical grievance burst into the open in late March. Brazilian news outlet UOL revealed that Brazil’s national intelligence agency, ABIN, had infiltrated the communications of some half a dozen Paraguayan officials involved in the Itaipu negotiations.”

TIL Of The Week

Chipotle is just a dried jalapeno! Who knew?

INFOGRAPHIC OF THE WEEK - Biggest Dams in the World

That’s all for this week! See y’all next week.