White Collar Unemployment, Abundance and Energy, Can a Country be Too Rich and More…

Notes from My Weekly Feed # 11

Quote of The Week (Credit: Morgan Housel)

I recently came across this quote from a world-renowned economist. It really puts things into perspective regarding AI and job loss. I thought it was worth sharing:

“For the moment the very rapidity of these changes is hurting us.

Countries that are not at the vanguard of progress are suffering.

We are being afflicted with a new disease… and that is technological unemployment.

This means unemployment due to our discovery of means of economizing the use of labor, outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labor.”

That’s John Maynard Keynes — in 1930!

It’s a good reminder that while there’s plenty of doom and gloom today about AI taking white-collar jobs, the anxiety isn’t new. Every wave of major technological change — machines, computers, and now AI — has triggered the same fear.

I do believe AI, especially if AGI arrives, will cause disruption. But just as Keynes couldn’t have imagined jobs like cybersecurity analyst, data scientist, or graphic designer, we can’t yet picture the roles that will emerge from mass AI adoption.

Want Abundance? Use More Energy and Then Get Efficient (Orca Sciences)

One of the best essays I’ve read in a while on the energy transition. Highly recommend! It mirrors how I’ve come to think about progress in this space.

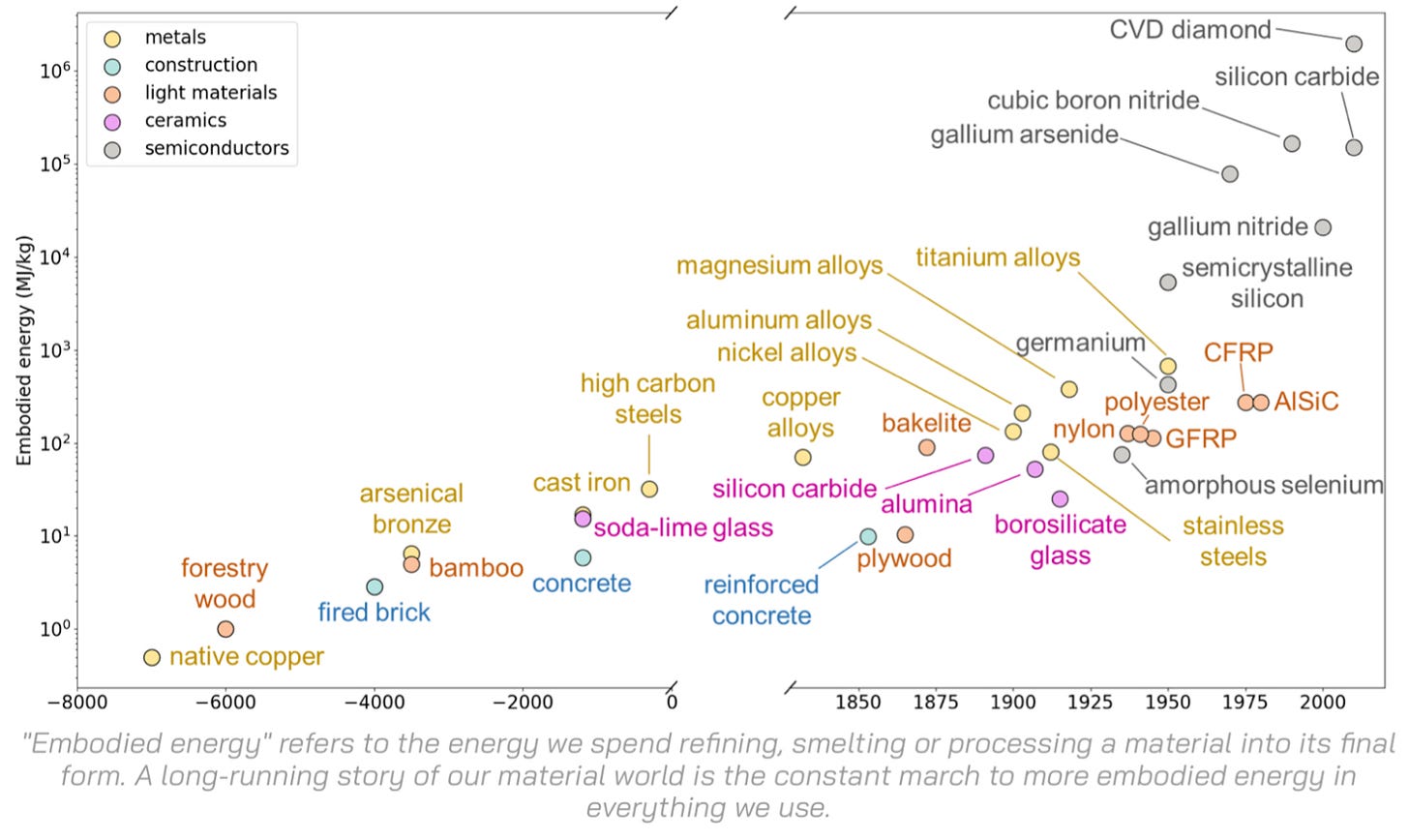

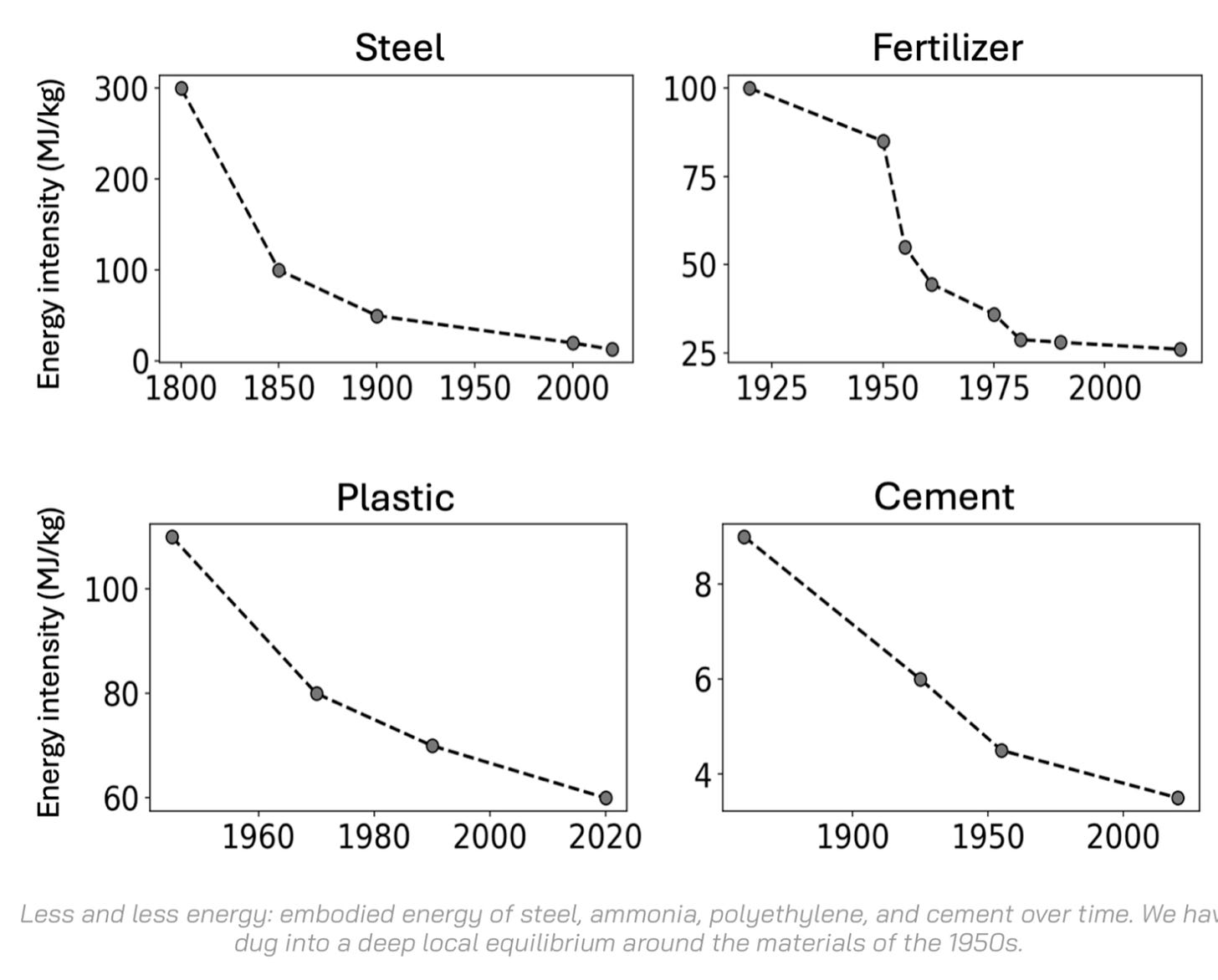

The core idea is simple but powerful: progress happens when we scale up materials that are more energy-intensive than what came before. From glass to aluminum. From timber to titanium. These materials are harder to produce at first—but they unlock real gains in strength, weight, toughness, or some other quality that makes them indispensable.

Then scientists hand off these materials to engineers—who bring the cost and energy curves of these materials down over time.

This cycle—first up the curve of energy intensity, then down the curve of efficiency—repeats again and again. If history holds, our future depends on cheap, abundant energy. That’s the foundation for building stronger, lighter, more useful materials—at scale. It’s also why we need an “all of the above” strategy. Maybe fission leads. Maybe it’s fusion. Maybe it’s something we haven’t invented yet.

Whichever path wins, the endgame is the same: get the marginal cost of energy as close to zero as possible. That’s how we unlock abundance and flourishing.

Can a Country Be Too Rich? (Source: Bloomberg, Fortune and ChartBook)

Well looks like Norway is just too rich - a good problem to have, I supposed?.

Norway’s main economic problem these days isn’t finding oil — it’s figuring out what to do with all the money. Think of it as the overachieving child of a very rich dad: it worked hard once, struck it big, and now fills its time with grand projects that don’t always need to exist. The country’s sovereign wealth fund has swelled into a $2 trillion trust, enough to insulate every Norwegian for several lifetimes. Which is how you end up with more sick days, lower test scores, and the occasional tunnel to nowhere — the hazards of having a fortune large enough to turn boredom into infrastructure.

Following excerpt from Bloomberg.

In 1969, Phillips Petroleum was poised to abandon exploration of the Norwegian continental shelf when the company decided to drill one last oil well — and hit the jackpot. The discovery made Norway one of the world’s richest countries. Its sovereign wealth fund, established to invest the money, now manages about $2 trillion, equivalent to roughly $340,000 for every Norwegian. For years, oil revenue and the wealth fund have helped this tiny nation to enjoy low unemployment, low government debt and a wide social security net guaranteeing a high standard of living. But recently, cracks have been starting to show. Norwegians are taking much more sick leave than a decade ago, driving up costs for health services. Student test scores have worsened more than in other Scandinavian countries, and critics of the government say there are too many boondoggle tunnels and bridges to nowhere. Amid creeping concerns that Norway is becoming bloated, unproductive and unhealthy, Norwegians have started to wonder: Can a country have too much money?

While on the topic of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund, its CEO Nicolai Tangen recently offered a pointed take on today’s market darlings. He noted that with the Mag-7 trading at historically stretched valuations, the downside risk likely outweighs whatever upside juice is left — a view that hints at a potential rotation in the fund’s positioning. It’s hardly a fully baked thesis, more a passing comment from an interview, but still worth keeping in mind if you’re thinking of doubling down on the group. For the record, I’m still long Mag-7 myself, but the combination of valuation and market concentration isn’t exactly helping me sleep at night. And yes, I say Mag-6 in my head — Tesla feels like a founder-story more than a stock, but that’s a tangent for another day (till then just imagine what happens to Tesla’s valuation if Elon Musk steps down versus what happens to Google maybe if Sundar Pichai calls it a day?).

“The best thing to do is always to do the opposite of everybody else,” Tangen told Bloomberg in an interview at Davos… What will that be today? Well, if you were to do the opposite of everybody else, it would be to sell the US tech stocks, buy China, sell private credit, just buy stuff that is out of fashion.”… In his interview with Bloomberg, Tangen did admit that taking a contrarian approach to investing meant accepting that your investing strategy would underperform at times, leading to investors questioning your sanity… “The concentration is absolutely worrying. It means that there is a risk in the stock market which we have never seen before,” Tangen told the FT’s Unhedged podcast… So there are very few companies tied into them, and they are getting bigger and bigger and more and more important.”

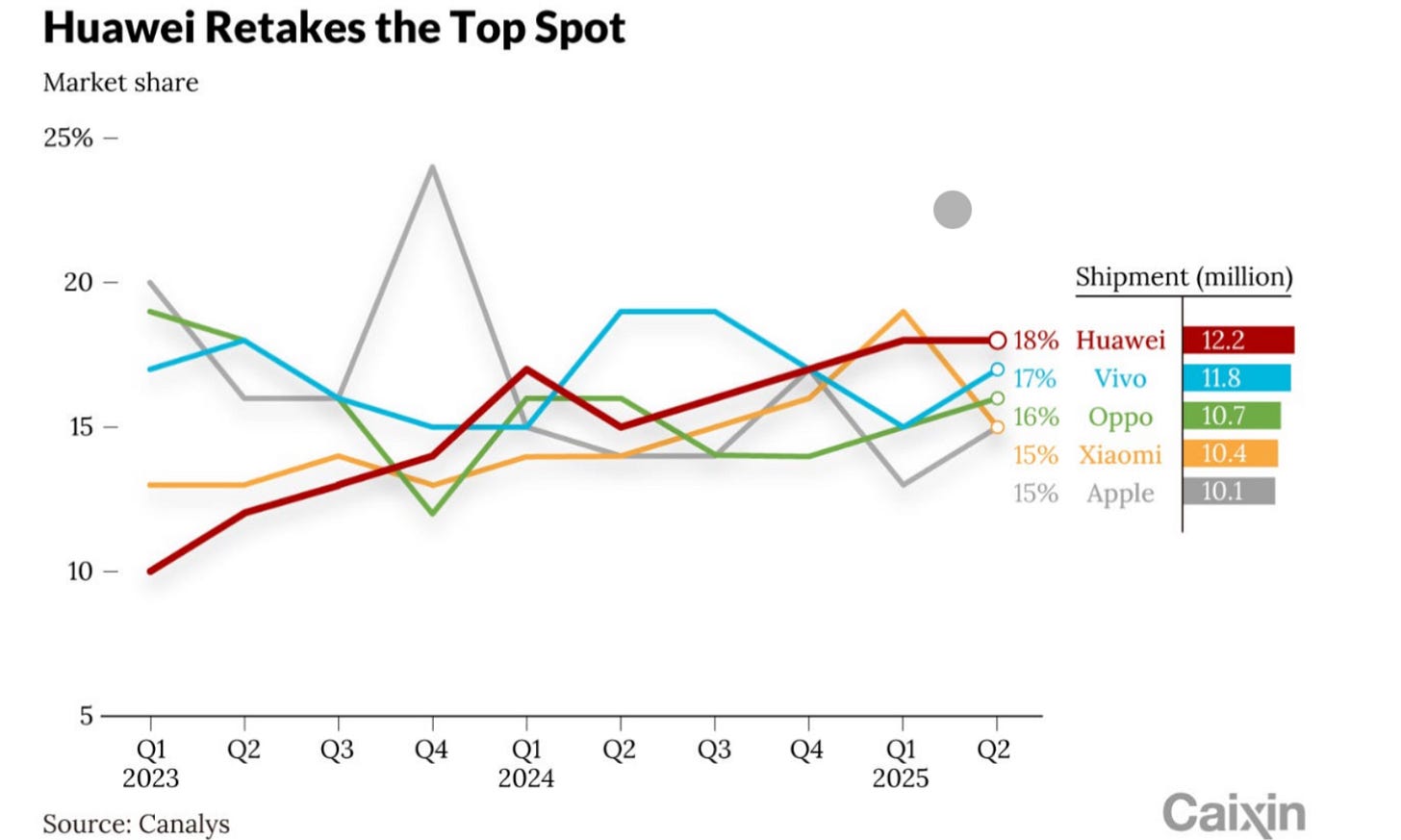

Chart of the Week: Smartphone Sales in China

This chart has been making the rounds as proof that Huawei is clawing back market share from Apple and the rest of the smartphone field in China. But look closer at the pattern. The sharp spikes in Apple’s share toward the end of Q3 each year aren’t random but they line up with its iPhone release cycle: September 2023 for the iPhone 15, September 2024 for the iPhone 16, and February 2025 for the iPhone 16e. Huawei’s latest flagship? October 2024. Which means this chart isn’t just about Huawei’s rise — it’s also about Apple’s stumble. The iPhone 16, and especially the 16e, failed to move the needle in China the way prior launches did. That’s a warning sign for a stock that’s already lagged the rest of the Mag-7. One more underwhelming product cycle — especially without a credible AI play — and many AAPL shareholders might finally have the conviction they’ve been waiting for to rotate out.

Beware of Bad Charts (World Bank)

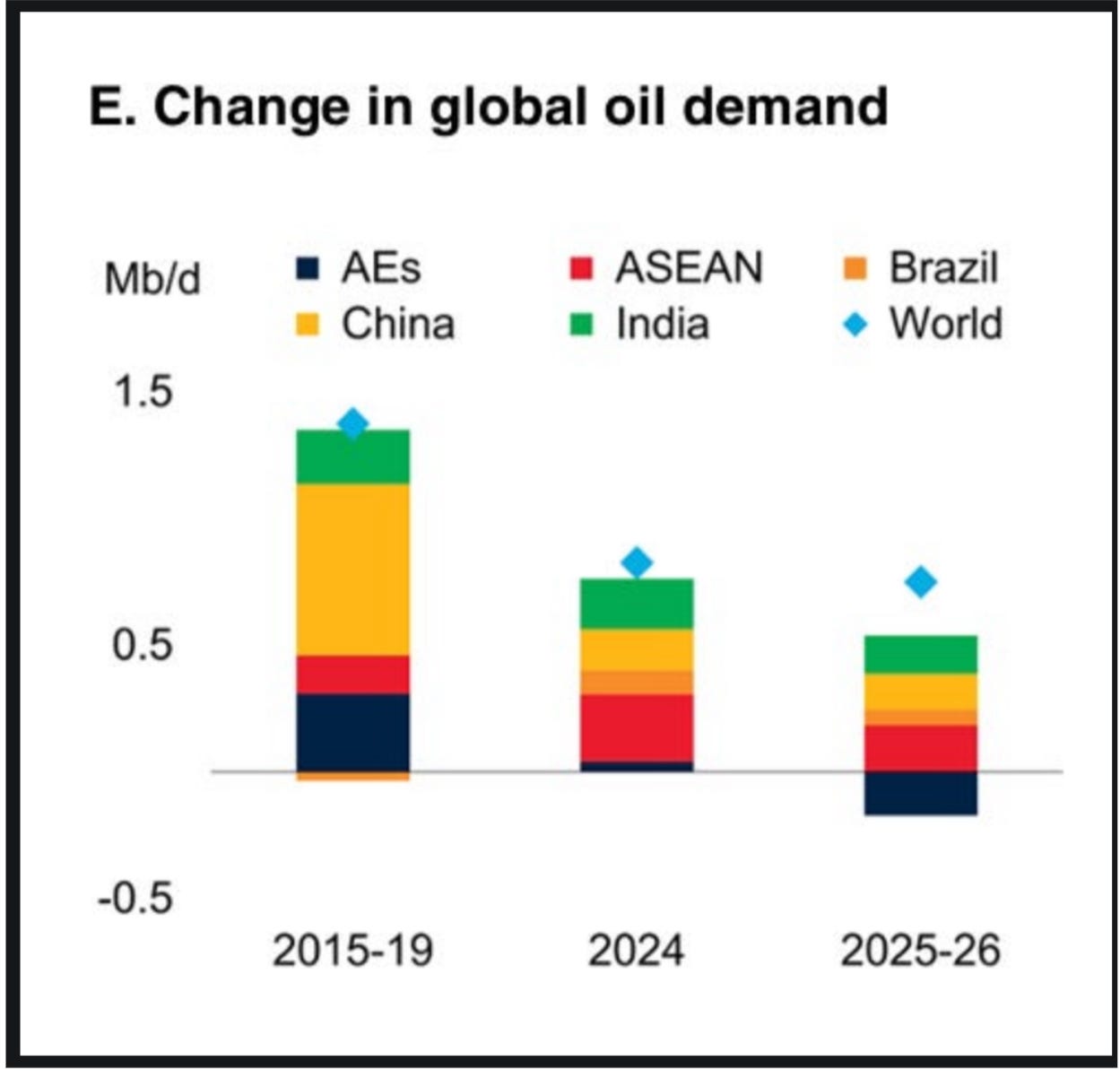

This World Bank chart tries to support that the recent drop in oil prices is due to lower demand.

The premise - slight drop in oil demand due to various macro factors - is certainly true. But it is not the only or the primary driver; other factors, specifically production hikes by OPEC+ have had a similar if not an outsized role to play here.

Anyways, the problem with the chart? Why compare change in 2019 vs. 2015 to (a) 2024 (vs. I suppose) 2023 and (b) 2026 vs. 2025? You either compare one year change or 5 year change - you should not, I think mix-and-match to fit your narrative. Also, change in “global” oil demand in two right bars - 2026-2025 and 2024-2023 seem flat (the diamond) but then you still see a drop in demand in the bars - why? Guess if you exclude the entire continent of Africa - then yes, you can fit the data to your narrative.

Bottom line: even World Bank analysts are human, and sometimes the framing misses the mark—and that’s okay.

Speaking of Experts…

If you don’t already, follow Dr. Roger Pielke Jr. on Substack. He’s one of the most widely cited voices on climate-scenario modeling and extreme weather, and he has contributed to IPCC work. The value of Substack here is hearing directly from the scientists doing the work, rather than a journalist’s compressed interpretation. That compression often strips nuance and tilts toward alarm, which then ricochets through the media until any request for clarification gets treated as heresy.

Some recommended reading: The Climate Beat Goes On, How I Became Voldemort in Climate Science

Again, I think I need to clarify that climate science has honest and real concerns. My general issue is how people, many times outside the field, can selectively use findings to browbeat alarmism and any request for nuance is then shunned as heresy. Dr. Pielke recently articulated this feeling way better than I could have.

“The IPCC is not a sacred text that can be used to identify believers and apostates. Weaponizing the notion of “mainstream” to dismiss or denigrate legitimate scientific views that one does not like is contrary to how science advances — through challenge, debate, discussion, and not gatekeeping.”

That’s all for this week! See y’all next week.